By Daniel Finkelstein

Daily Mail

18 January 2009

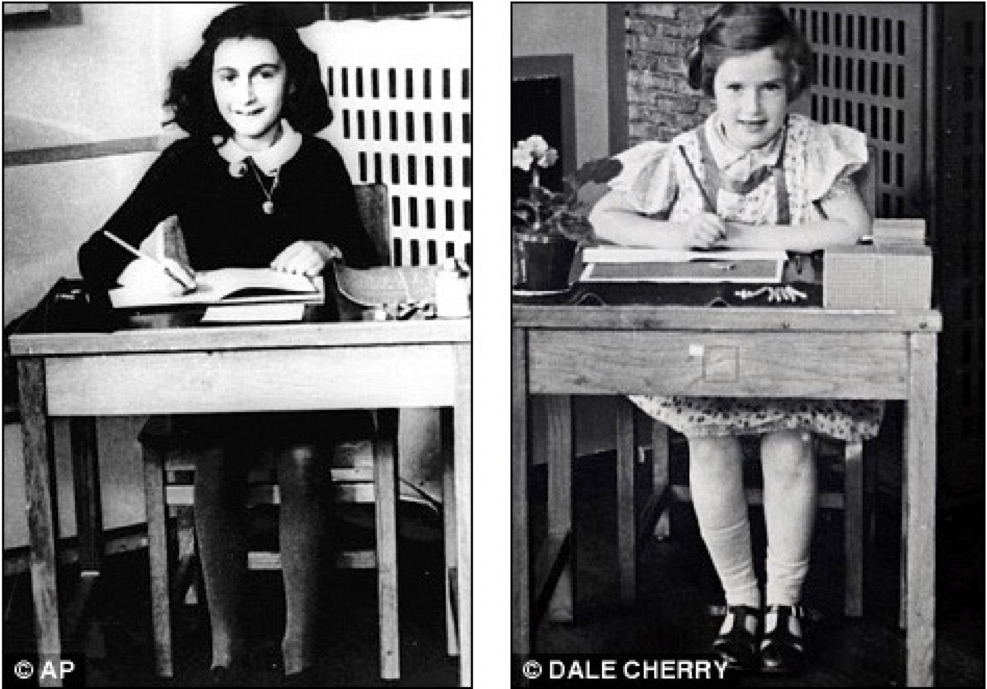

She is a symbol. An icon of the Holocaust. That picture of Anne Frank at her school desk in Amsterdam, pen in hand, is so eloquent, telling of innocence that was lost.

Her diary, which shines bright with her personality and her precocity, makes the fact that she died in Belsen unbearable. She speaks as no statistic can speak.

But for my family, Anne Frank will always be more than just a symbol. For us she is something that is, in a strange way, almost more powerful.

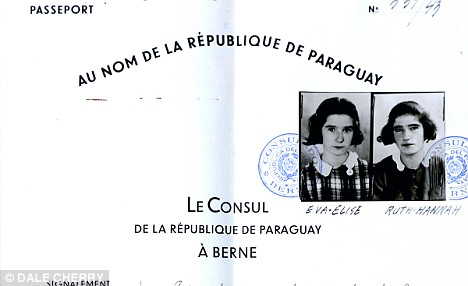

Different fates: Anne Frank, left, and Mirjam Wiener pose for the camera at the Montessori school in Amsterdam where they were both pupils

For us she is just a little girl, who lived her life and died not as a celebrity but as part of a community now long gone. A community starved, murdered, scattered to the winds.

She is this to us because my mother, Mirjam, and her sisters, Ruth and Eva, were part of that same community. Like the Franks, they were children of a man decorated as a German officer in the First World War.

As little girls they played on the same streets as Anne and Margot Frank and went to the same schools.

My mother and her sisters, too, sat at an Amsterdam Montessori school desk with their pens to have their pictures taken. They went to Hebrew classes at the Jewish Liberal Community Synagogue, where the Franks were members.

And just like Anne and Margot Frank, Mirjam, Ruth and Eva Wiener were inmates of Belsen.

The Diary Of Anne Frank has become such a powerful statement of the crime against the Jews that there are some who rather desperately deny that it is true.

They claim Anne Frank is a fiction, that there never was such a girl and she did not die in Hitler’s camps.

But my mother can bear witness. For she knew Anne Frank. And she was standing by the wire in Belsen on the day Anne and Margot arrived in the place where they were to die.

She saw them arrive and remembers the details to this day, even though at the time there was nothing remarkable about the Frank girls.

She recalls their arrival because my Aunt Ruth had been excited.

Ruth was at secondary school with both Anne and Margot and she had been learning Hebrew with Margot. One day, after the war had begun and the Nazis were occupying Holland, the two girls had been called out of lessons.

The synagogue was deserted but a young couple had arrived. They were to be married as Jews in secret. My aunt and her friend acted as bridesmaids.

So when, in the autumn of 1944, Ruth saw Anne and Margot arrive she pulled out her little notebook, the pocket diary she kept despite it being forbidden.

And with her tiny pencil she wrote down the fact that the deniers still try to deny. That Anne Frank and her sister had entered Belsen.

When I was a boy, though, I did not know anything of Anne Frank. The story that made an impact on me was the story of the scooter.

My mother was born in 1933 in Berlin. Just after her birth, her father, an early campaigner against the Nazis, was called to a meeting with Hermann Goering.

Shaken by the exchange, he moved his family to Amsterdam. And there the family lived on Jan van Eyckstraat, in the river area, in a two-bedroom house.

They lived an ordinary life, a happy childhood playing on the streets with their school friends. But when my mother was only six years old, there came war, and everything changed.

Her father went to London to carry on his work documenting the Nazis – work that ultimately helped secure convictions at Nuremberg. He obtained visas for his family to join him, but it was too late.

The Wiener girls and their mother were still in Amsterdam when the Nazis arrived. And that’s where the scooter comes in.

You see, my mother was given a beautiful blue scooter for her eighth birthday.

‘It wasn’t like the ones you see now,’ she says. ‘It had thick wheels and a big running board. It was my pride and joy.’

It was 1941, the Wiener family lived in Amsterdam and the Jews were not allowed on buses or trams.

‘It became the family Rolls-Royce,’ she says. ‘We took it everywhere.’

But by 1943 the Nazis were clearing the city of Jews area by area. On June 20, it was the turn of my mother’s family to be forced out on the street and taken to the cattle trucks.

‘As we stood there, I managed to whisper to one of my neighbourhood friends that she should take my scooter,’ she recalls. ‘I was pleased to have done that. But, of course, I never saw it again.’

As a child, that was a story I could understand. And I had my mother tell it to me again and again. Actually, if I am honest, I still get her to tell it to me.

The cattle trucks took my mother, her two sisters and my grandmother to Westerbork concentration camp. The place, incidentally, where the Franks were also taken.

‘Westerbork,’ says my mother, ‘was terribly crowded but although the food was poor we were not starving. I used to cry all the time, which was all my poor mother needed.’

And every Tuesday there was a transport to Auschwitz.

‘I was only ten years old, but even I knew these transports were something terrible. As a grown woman on a trip to Poland, I was asked if I would like to visit Auschwitz. I was startled to think that it had a physical location. It’s was as if someone had said, “Let’s go and visit Hell. It’s only ten minutes away, fifth exit off the motorway.”’

In the end, as was inevitable, members of my mother’s family found themselves listed for the Tuesday transport.

My mother recalls how she said goodbye to her aunt and uncle and to her 14-year-old cousin, Fritz. And she still has the pitiful letter from her aunt promising that ‘we will meet again’. But, of course, they never did.

Some Holocaust deniers believe that Jews didn’t die in the gas chambers. They think that people like Fritz and his parents survived and are living in Israel. In which case, the joke is over: they can come back now, don’t you think?

The next week the Wieners themselves were slated to leave. But somehow, and my mother is not sure how, their names were taken off the list. Instead, they were transported to Bergen-Belsen.

‘Belsen was bleak and what I remember most is that it was terribly cold,’ she says.

‘That and the starvation diet. And the counting. The Germans were forever counting us. Preferably in the middle of the night. Preferably involving beatings.

‘My elder sister had to work. But I spent a lot of the day sitting around as we were too weak to do anything else. Whenever we could, we went to the back of the camp with our spoons and tried to scrape the remains from the empty food barrels which, even when they were full, had only contained watered-down turnip.’

The girls used to spend time, too, watching the next-door camp section through the wire, even though this was strictly forbidden.

Occasionally, they saw people they knew. And that is how, one day, they saw Anne and Margot.

The Frank girls died in Belsen. My mother and her sisters were more fortunate.

Thanks to false Paraguayan passports that their father had obtained for them, in January 1945 the family were part of a prisoner exchange. It was incredibly rare, a piece of amazing luck, but then survivors’ stories almost always involve some stroke of luck.

The family was marched past the camp doctor and told they were to be given a shower.

‘I didn’t fully understand why until later,’ says my mother, ‘but people were terrified. We stripped our clothes off, walked into the shower room and waited. Then water came out. It was hot water, too, the first time we’d felt that. Later we were given soup. It had actual pieces of potato in it. That, a child remembers.’

A child remembers, too, what happened next. My grandmother thought little of her own welfare.

Every scrap of energy, every scrap of available food, she gave to her little girls. So they should live, so they should survive, so they should be free.

And by the time that the prisoner exchange happened, my mother’s mother was very ill. Almost too ill to stand.

The Nazis had been anxious not to let any sick people on the transport. But, even though she was dying, my grandmother held herself upright long enough to get on to the train.

She managed that act of courage and stamina because she knew that without her, her girls could not go.

They hadn’t been on the train for long when the guards changed their minds. They decided they had too many Jews for the exchange.

A guard walked through the compartments throwing people off, many of them to die, freezing, in the snow outside.

When he got to the Wiener family, to the sick woman and her three young girls, he told them, too, to get off the train.

The girls pleaded with him that their mother was too ill to move. He shrugged his shoulders and moved on. On such whims were lives lost or saved.

So my grandmother saw her beautiful children to freedom. She saw them across the border to Switzerland. Safe. And then, not many hours later, my grandmother died.

Thus it was that three girls, quite alone, came to be on a Red Cross ship heading towards the Statue of Liberty in early 1945, heading to Ellis Island to seek refuge in America.

They carried with them their father’s German medals from the First World War, medals my grandmother had kept throughout their detention.

She had thought that perhaps these wartime decorations might do them some good, would prove that they were good Germans even though they were Jews. They had been no use at all.

Beyond Ellis Island lay the promise for the girls of a reunion with their father, who had evaded Nazi imprisonment.

But first, they knew they would face a tough interrogation because the Americans feared that their boat contained German spies. What, they asked each other, would their interrogators make of these medals? Would they be prevented from entering?

They wrapped the Iron Crescent and the Iron Cross (2nd class) in a handkerchief, opened a port window and, as they passed the statue, dropped them off the side of the boat.

And there they lie to this day, in the deep, at the foot of that great monument to freedom. When I go to New York, I take care to visit them.

After the war, my grandfather took his girls to live in London. They bought a comfortable house in Golders Green and started rebuilding their lives.

Alfred Wiener turned his Nazi archive into one of the world’s most important libraries on fascism.

And one day, in the early Fifties, my mother and he received a visit from a lonely man, who had also begun to rebuild his life. Otto Frank came to see his old neighbours and to talk about his daughter’s diaries.

Last Friday, just like every Friday, my family gathered together at my parents’ house.

Surrounded by her grandchildren, my mother lit the candles to usher in the Sabbath.

They are lit as a religious obligation. I suppose they might also be seen as candles of mourning, lit for those millions, like Anne and Margot Frank, who are not here to light them for their own grandchildren.

Yet we prefer to see it differently. As the little children pass round the challah bread, our candles shine in celebration.

That Hitler failed. And that we all live in peace and security in this wonderful country.

This article first appeared in the Daily Mail.